We will now take a look at the fine details of a sword blade design: Blade Sharpness, Edge, Grind, Taper, Ricasso, Choil, & Fullers. Most of these important details really separate mass-produced swords from real weapons. Let’s take a closer look at them and how they affect you.

Blade Details: Sharpness, Edge, Grind, Taper, Ricasso, Choil, & Fullers

Blade Edge: Sharps and Blunts

Sharp: Sword with a sharpened cutting edge.

Blunt: Sword with a cutting edge that is not sharp.

Blade Sharpness: How blunt or sharp the blade is.

Historical Hudiedao were intended for actual combat including fighting individuals equipped with a shield and armor. While they were well sharpened, the cutting edge could not be razor fine because it would too easily nick. For weapon vs. weapon practice, a blunt edge is preferable both to increase its useful life and to avoid needless danger. A really thick rounded edge will last the longest but the sword looks ugly and behaves differently due to weight and balance.

A good number of martial artists practice with a sharpened Jian because they can feel the difference in balance and behavior between blunts and sharps. Jian are long narrow straight swords, with even slight differences potentially noticeable due to leverage, whereas Hudiedao are shorter and wider. One is a race horse, the other a working equine.

While there is a major difference in feel between a Butterfly Sword that is essentially a toy and weapons-grade, the difference in behavior between EWC’s true weapons arising from blade sharpness will almost always be immaterial, an exception being thicker edge blunts designated for heavy training. The standard EWC/Modell Design blunt generally has a 1 mm edge and is ground so that it looks sharp to bystanders. EWC’s new training swords have a 2mm rounded edge for additional durability. We do not make the same assertion with products by other vendors since their blade may be a simple sheet of steel with the cutting edge of a blunt the same width as the flat.

TIP: Be careful of Butterfly Knives of unknown origin, especially sharpened blades, if you value having all your original body parts. If you can see that someone else is practicing with sharps, you are in the wrong room!

Sharpened Butterfly Swords that are true weapons can easily cut through tendon into bone with a single lapse of concentration and should be used for display and self-defense only. Sharpened low quality swords are even scarier since the blade has a realistic chance of flying off the handle. The danger of practicing with sharpened Butterfly Swords is not an urban myth; there is a post on one of the Knife Forums by an individual who cut his own tendon with a non-EWC product. We recommend only blunt BJD for training to help assure the safety of students and individuals in their environment.

The great Japanese Samurai Miyamoto Musashi won many sword duals by killing his opponent with a single blow from a rounded wooden training sword. Our blunts are true weapons, remain inherently dangerous and must be treated seriously.

Blade Cutting Edge

The cutting edge of a historical Butterfly Sword runs the full length of the blade from the D Guard to the tip. Benny Meng and Richard Loewenhagen write that Shaolin Monks preferred to avoid killing and so only sharpened the 3” of cutting edge closest to the tip leaving the remainder blunt. War Era knives suffered no such scruples.

In Western saber fencing, the strong half of the sword edge closest to the hilt (some define it as the bottom third of the blade), known as the “forte” and traditionally used for defensive parrying, is left unsharpened. The same is true of some antique Hudiedao, but most are sharpened along the entire edge from guard to tip. In Hung Gar gung fu, the philosophy is to block with whatever part of the blade or “D” guard is handy. Since you cannot leave the entire edge unsharpened, there is little reason to leave the forte dull. Jeffrey Modell, Esq., History and Design of Butterfly Swords, Kung Fu Tai Chi magazine p.59 (April 2010).

In nearly all cases the spine is flat – there is no grind. Red Boat Era knives were designed for killing and had a swage.

Swage: A ground area on the spine of the knife commencing at the tip.

Swages are frequently blunt, the grind being sufficient to reduce the tip so as to concentrate force in a smaller space and ease penetration without removing much supportive steel. A blunt swage tends to push the blade down onto the primary cutting edge so it can do more damage. A sharpened swage is itself a cutting edge that can be used for a deadly reverse cut that can disable a hand in the blink of an eye. The trade-off is that the thinner edge is more easily damaged.

Blade Grind Profiles

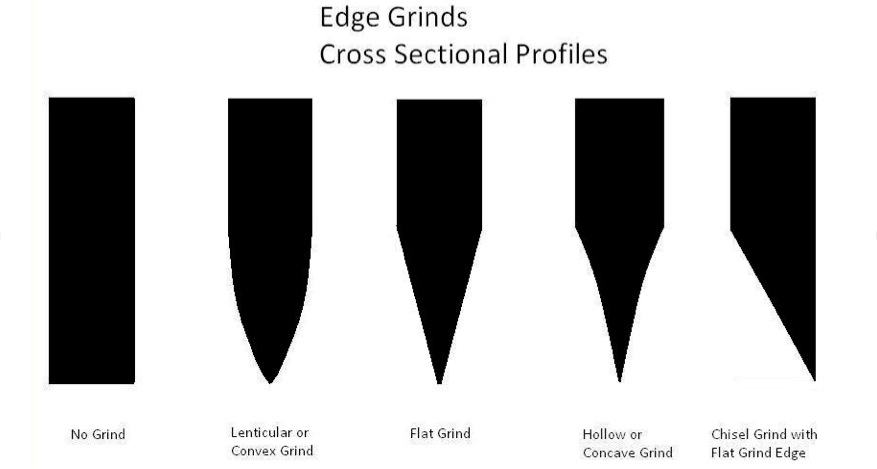

Blade Grind: Type of grind used on the cutting edge

Traditional Butterfly Swords had a lenticular (convex) grind that has extra steel supporting the cutting edge to minimize nicks when the knife hits bone and other hard targets. More precisely, a single or pair of full handle Hudiedao would have lenticular grind blades, but 2-in-1 swords, which are mirror image swords that when held in one hand look like a single weapon, had a chisel grind with the inside edges a flat grind and the outside edges convex.

A chisel grind has the twin the advantages of being easy to make and sharpen. The downside is that the flat interior side generates significantly less drag than the outside so the knife cuts on a diagonal toward the flat side rather than straight.

While at least one wag has opined the traditional chisel grind was intended to increase the damage when penetrating the rib-cage, we believe you are better off being able to hit the intended target. Modern practitioners prefer a pair of blades each of which has the major grind on both sides. The chisel grind may have been adapted because it takes less talent and effort than grinding two sides of a blade with perfect symmetry, important factors for weapons made by a village smith for locals.

A hollow (concave) grind allows for the finest possible cutting edge – the sharpest cutting edge – and is therefore best for use against soft targets like flesh. Done well a wide hollow grind is extraordinarily beautiful, and a feature commonly requested by clients purchasing expensive custom Butterfly Swords. The problem is the hollow grind has far less steel supporting cutting edge.

A hollow (concave) grind allows for the finest possible cutting edge – the sharpest cutting edge – and is therefore best for use against soft targets like flesh. Done well a wide hollow grind is extraordinarily beautiful, and a feature commonly requested by clients purchasing expensive custom Butterfly Swords. The problem is the hollow grind has far less steel supporting cutting edge.

We design some models with a combination of grinds to offer the beauty of a hollow grind with the strength of a more purpose-specific grind by the cutting edge. Compound grinds require more skill and work.

The grind should be selected based on the use. If the intention is just display, then a traditional grind or wide hollow grind are fine choices depending on your preference.

A wide hollow ground stainless steel blunt blade is the best choice for BJD used solely for individual practice and solo demonstrations for aesthetic and maintenance reasons. We would prefer a wide blunt cutting edge on hammered spring steel for a two person demonstration with choreographed heavy contact assuming wood trainers fail to impress. Optimally hardened D-2 is more likely to damage opposing equipment.

TIP: Free sparring with Butterfly Swords is nuts. Even our blunts are true weapons and inherently dangerous.

The general design of a chopper BJD is already pretty good for defense against a tree but if your intention is cutting exercises, the steel and grind should be designed for that purpose rather than combat or training. An ugly flat sheet of medium carbon steel, well polished and uncoated to slide through easier, with a squat flat grind edge is a pretty smart choice from toughness and cost perspectives.

Blade Taper

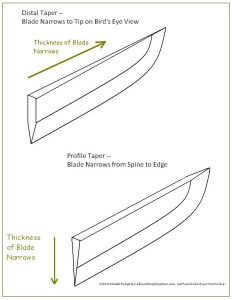

Distal Taper: Generally means the blade thickness gets thinner toward the point.

Profile Taper: Blade thickness gets thinner toward the cutting edge.

Tapers adjust the weight, point of balance and handling characteristics of a blade.

A taper can turn an otherwise ungainly piece of steel into an elegant weapon. War Era  Hudiedao exhibited both distal and profile tapers. While some blade styles and lengths can be crafted to a properly balanced combat weight using an expert grind, a lot of our work relies on tapers.

Hudiedao exhibited both distal and profile tapers. While some blade styles and lengths can be crafted to a properly balanced combat weight using an expert grind, a lot of our work relies on tapers.

Most modern Butterfly Swords are a flat sheet of thin cheap steel with perhaps a small grind area to save manufacturing costs. Not a problem. No amount of tapering could rescue a good chunk of these poor designs. Adding a taper to a Butterfly Sword obviously increases its cost. On high end swords the work is done by hand and a major reason for two blades of a pair to differ somewhat in precise weight.

Blade Ricasso and Choil

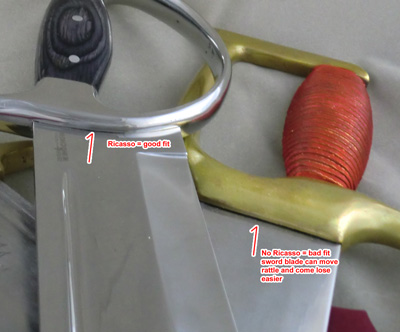

Ricasso: The unground area of the blade between the D Guard and the ground area of the blade.

Choil: The area of the blade between the cutting edge and the tang, frequently but not necessarily cut-out, ground or otherwise shaped.

War Era Hudiedao typically had a cutting edge that went all the way to the front of the D Guard. That is where the blade steel, except for the tang, would stop. Put another way, most of the blade was not secured to the D Guard. A number of modern Butterfly Swords recess the base of the blade into a slot in the D Guard. In most cases the fit is loose. Our work has an extremely tight fit that helps hold the blade in the D Guard. Using the D Guard to further support the base of the blade is an important improvement over traditional construction methods.

A Ricasso helps assure a good fit by providing a rectangular cross section that fits into a simple rectangular slot. The hard part is getting the tight fit. The base of the blade needs to start out slightly thicker than the slot and there is a blade inconveniently located where you would like to grab when doing the fitting.

The thick blunt bottom edge of the Ricasso, or Choil, is less likely to nick if used to counter a serious impact head-on. Some marital artists put a finger on the Choil or run one past the Choil on its way further towards the center of the blade, so for them it is important that the first few centimeters of the blade either be unsharpened cutting edge or Choil. Blunting this cutting edge is obviously of little concern on BJD that would normally be unsharpened on part of the cutting edge for covering or blocking but some schools like to slide their swords down an opponent’s staff along the D Guard. Having a Choil eliminates the sharp edge that would otherwise be there but it is still no fun having a small piece of steel rammed into your index finger.

Modell Design occasionally adds modern flourishes to FOS Butterfly Swords such as a Choil shaped into a half circle, quarter circle or tear drop (see picture of Sifu Wayne Belonoha’s knives under the “Cutting Edge” section). The purpose of a Choil on a knife is to make it easier to re-sharpen the knife without getting on odd spot at the grind termination. A Butterfly Sword Choil can be designed, however, to help slow the opponent’s weapon from sliding off the knuckle bow.

Blade Fullers

Fuller: A groove or slot running along the blade.

The purpose of a fuller is to lighten the blade without sacrificing strength, maintaining rigidity despite the removal of material (like an I-beam). Contrary to popular belief, it is not to stop a vacuum from keeping the blade stuck in an opponent. Americans sometimes (incorrectly) call fullers “blood grooves.” While a true fuller does make it easier for the target to bleed out, that is incidental to the actual purpose. To be functional the fuller must be deep enough to actually impact the weight.

Throughout history, swords have been made with no fuller, a fuller on one side, a fuller on both sides, or more than one fuller per side. Very few antique Chinese Hudiedao required or exhibit fullers because of their relatively short length and tapering. Think about the differences between a Butterfly Knife and a huge European medieval sword or a Napoleonic saber. Given the improved steel quality and reduced length of modern BJD, fullers are even less of a necessity but can add to the aesthetic of the design and help control weight.

A lot of the fullers on modern Butterfly Swords are so shallow that their sole ability is decorative. Decorative fullers are more typical on thinner blades. They are comparatively easy to add, especially if one end is run into a shoddy D Guard slot since only the other end need be finished. Running a channel into the D Guard, creating an open space, creates a channel for liquids and debris facilitating rust on the tang, which cannot be cleaned.

TIP: Decorative fullers say something about the owner’s lack of expertise.

This video is Part 4 of 10 on Choosing Butterfly Swords by Jeffrey Modell. This video goes along with the blog article, but does not follow the exact same order of topics. We apologize that the AUDIO is OUT OF SYNC. This is the way the camera filmed the footage, so there is little we can do about it (simple aligning will not work). We hope you get some benefit, regardless:

[youtube]http://youtu.be/HpJbdo2BGRk[/youtube]

Your half way done! Go Here to Read About Blade Finishes and Coatings

One thought on “Choosing Wing Chun Butterfly Swords – Part 3 – Blade Details”